The Profitable AI Agent Blueprint No One's Talking About

2025 was billed as the year of Agents! Everyone on YouTube, X and Reddit wants to build AI agents that print money. But we’re at the end of the year and surprisingly, there isn’t a clear pathway to success and no one knows where to start (including us!).

This is where we found ourselves until recently. Lost and confused. The X demos look magical : the coding agent that builds your app, the browser agent that books your travel, or analyst agent that presents insights with a single prompt. But we soon realised that the gap between a sparkling prototype and a profitable deployment is where many of our projects ended up. They automated the wrong things, they aimed too high (and failed catastrophically) or aimed at small tasks which barely saved anyone time! We realised that agents are not drop-in replacements for humans but rather precision tools for specific economic opportunities.

In this state of confusion and despair is when we came across a couple of research papers that seemed to illustrate a path to profitable agents. The roadmap that emerges acts as a very clear path, so much so that it feels like cheating! They illustrate exactly which roles to target in the economy, how to implement agents that actually work, and where humans remain indispensable. We see a playbook emerging and wanted to share it with the world to request feedback and see if it rings a bell.

The Economic Targeting System

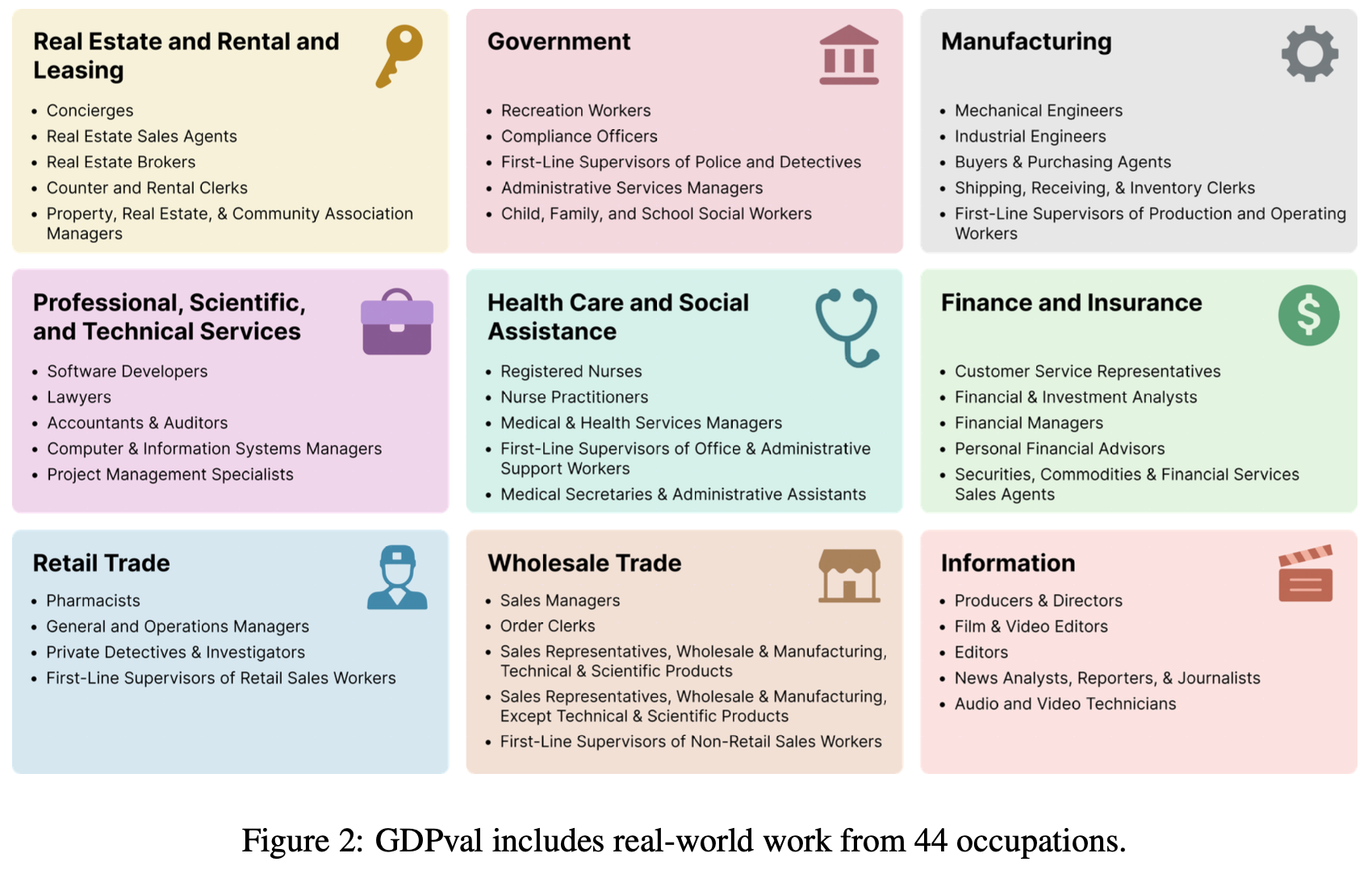

The first paper that is published by OpenAI is called GDPval - a dataset that tracks economically valuable industries and provides examples of tasks done by experts in high-paying roles within these industries. Instead of inventing synthetic benchmarks, they asked: “What digital jobs actually matter to the US economy?” They mined the Department of Labor’s database, filtered for occupations that are both high-paying and digitally focused, then had actual experts in those roles create representative tasks.

The authors of GDPval recommend the following 9 broad industries and 4-5 specific occupations within those industries. As an illustration: they say that the role of an Accountant as part of the Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services industry is highly valuable commanding a total annual compensation of $135.44B across the industry.

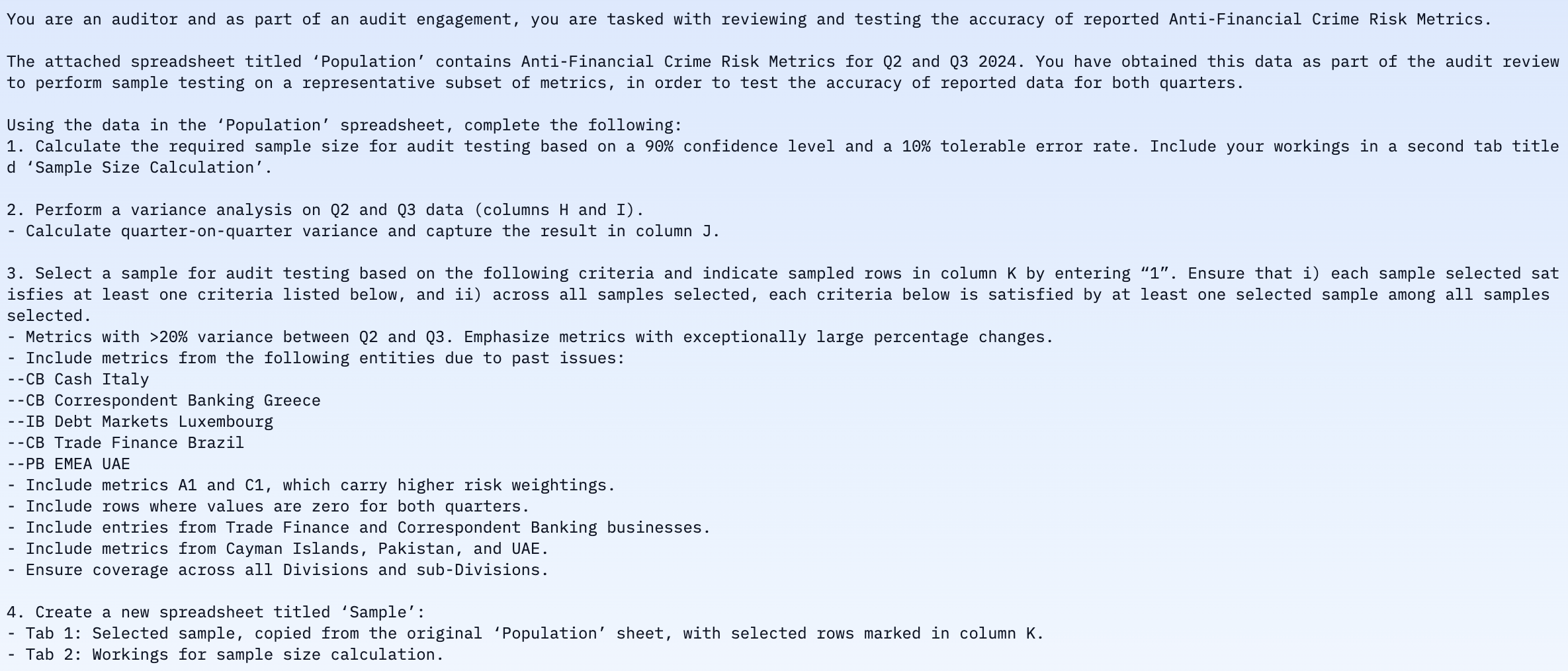

For each identified occupation, they create examples of representative tasks that someone in this role would be asked to do on a daily basis. These tasks are created by real professionals working in that occupation and undergoes multiple review rounds to make it realistic and complete. An example of such a task for the Accountant is as follows:

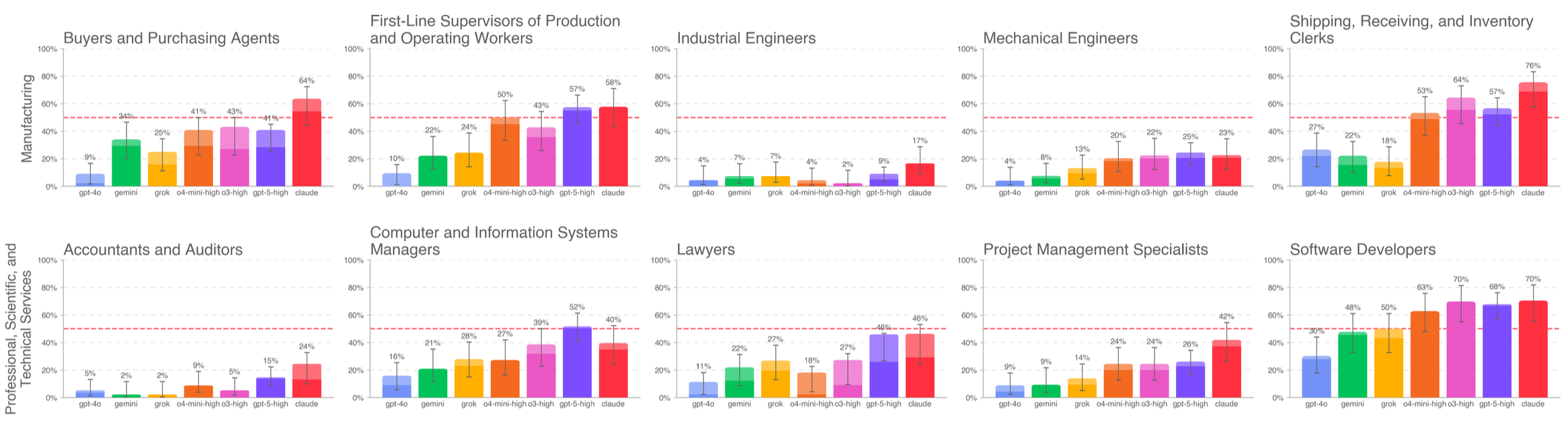

Finally, they test the performance of frontier LLMs on these tasks and ask experts in that area to compare the task results of various LLMs to the results produced by human experts with an average of 14 years of experience. Overall, Claude Opus came within striking distance of human parity across the board. These models are still not as good as humans across all tasks but the the headline number is just an average. The real insight is in understanding the success rate by occupation as you can see in the graphic below -

What you notice is that AI has already surpassed human performance in specific, high-value roles like:

- Shipping, Receiving, and Inventory Clerks [total compensation of $38.50B]

- Buyers and Purchasing Agents [total compensation of $39.79B]

- Software Developers [total compensation of $239.18B]

This tells you which specific occupations to target for agentic automation. It now becomes clear why every high-valued startup (Cursor, Replit etc.) are chasing the coding agent market which happens to be the largest by total compensation. But don’t get distracted, each occupation on this list is a concentrated pocket of economic activity worth hundreds of billions in total compensation. The paper essentially created a heat map of automation opportunity weighted by market size.

Playbook: find the occupation that has already achieved or is close to human parity, see if it has an appealing total market size (by compensation) and determine if that is personally exciting for you or your team to chase after.

This is your targeting mechanism. Most companies waste resources automating low-value busywork because it’s easy. The GDPVal framework forces you to hunt where the economic prey is actually concentrated.

The Implementation Framework

Identifying a target is only the first step. The real trap is believing you can stitch together a bunch of LLMs, fire-and-forget a prompt and walk away with millions in the bank.

Modern work doesn’t happen in a single turn. It’s iterative. A software developer doesn’t just write code - they review requirements, ask clarifying questions and adjust to feedback. There’s also a lot of context that an employee who works at a company accumulates. Most of which is not codified or explicitly documented anywhere. A purchasing agent doesn’t just place an order; they compare and choose vendors but they also remember how the experience with a particular vendor was the last time. They also remember that their boss is on particularly good terms with the more expensive vendor. This is context your LLM will never have.

Even if you stuff a prompt with context, you’re fighting the fundamental nature of how humans solve problems: through loops, UI navigation, and incremental refinement. This is why so many agent deployments end up as expensive demos instead of profitable systems. And that’s where our second research study can help.

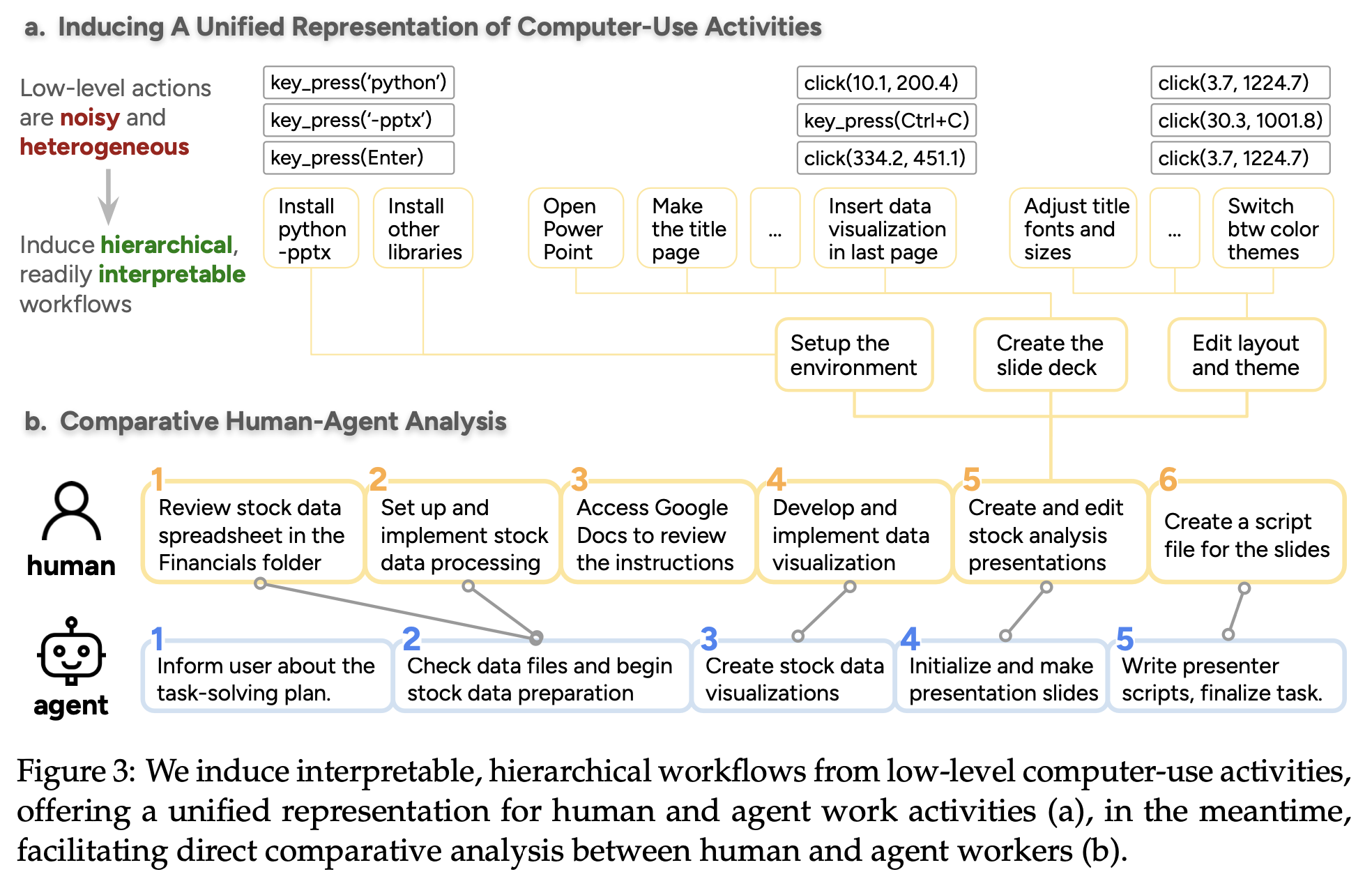

In the paper, “How Do AI Agents Do Human Work” the researchers use the same Department of Labor data but attack a different problem. Instead of asking “How well does an AI agent do this task?”, the authors asked “How do AI agents approach work differently than humans?”

In order to answer the question, they asked human experts and AI agents to perform the same task. But rather than focussing on final results and task completion, they paid more attention to how a task is broken down by humans and agents, which tools are preferred by each of them and how fast and accurately they perform. This methodology is the key thing to take away from this paper.

Three critical insights emerged:

1. The UI vs. API Divide - Humans navigate through interfaces. Agents instinctively reach for programmatic solutions. This seems like an advantage until you realize that most enterprise systems don’t have clean APIs, and agents waste enormous compute trying to hack around UI constraints they don’t understand.

2. The Overconfidence Problem - Agents would rather hallucinate a solution than admit “I don’t have enough information” or “This task is beyond my capabilities.” Humans are naturally cautious; agents are reckless optimists. This creates catastrophic failure modes in production.

3. The Task Decomposition Goldmine - In order to support their methodology, the authors make use of a tool that observes a human as they perform a task. They record screenshots and clicks and use this to create a workflow mapping tool. This is very important because it is able to translate the way a human being breaks down and performs a task and convert it into a clean task hierarchy, which provides you the exact breakdown to feed and orchestrate an agent. This transforms prompting from guesswork into engineering.

Crucially, the paper also identified which tasks agents clearly dominate and which remain human strongholds. Not everything should be automated, and this framework shows you precisely where to draw the line.

The Profitable Agent Recipe

One of these papers shows you where to aim; the other tells you how to hit the target. Combined, they form a clear blueprint for building agents that actually deliver ROI:

Step 1: Target with Economic Precision

Use the GDPVal methodology to identify roles where:

- AI performance is at or near human parity

- Total compensation is concentrated and large

- Tasks are digitally executable

Software engineering is obvious, but the same logic reveals under-the-radar opportunities in procurement, data analysis, and customer operations.

Step 2: Map the Actual Workflow

Before writing a single line of agent code, capture how your best humans actually perform the target tasks. Use the second paper’s framework: record the clicks, the navigation, the decision points. Reverse-engineer this into a structured task decomposition.

Step 3: Engineer the Human-Agent Division

This is where most projects fail. They try to automate the entire role. Instead, based on the task analysis and findings from the second paper try to create a surgical division of labor:

- Agent handles programmatic tasks, API calls, data processing

- Human handles exception cases, UI navigation requiring judgment, and quality gates

The goal isn’t replacement; it’s amplification. Your agent should make your best human 10x more productive on the highest-value parts of their job.

Step 4: Prompt from Evidence, Not Intuition

Use the captured workflow data to create prompts that mirror the actual task structure. If the human breaks a purchasing task into “vendor research → price comparison → approval routing,” your agent should receive that same decomposition, not a monolithic “buy this for me” instruction.

Iterate on the prompt using the workflow map as your guide. When the agent fails, you don’t just tweak random words - you identify which step in the human workflow wasn’t properly translated.

The Uncomfortable Truth

The winners in the AI agent race won’t be those with access to the best models. Every major API is a few clicks away. The moat is in the mapping i.e. understanding the economic terrain and translating human workflow into agent architecture.

The future isn’t human vs. machine. It’s humans using machines like tools; just like we’ve always done from the stone age to the AI revolution.

Does this resonate with you? Drop us a few lines if you’re already successfully followed this path or have a very different take!